Any Oakley

- Matthew Kerns

- Sep 15, 2020

- 5 min read

I bet you didn't learn this one in school.

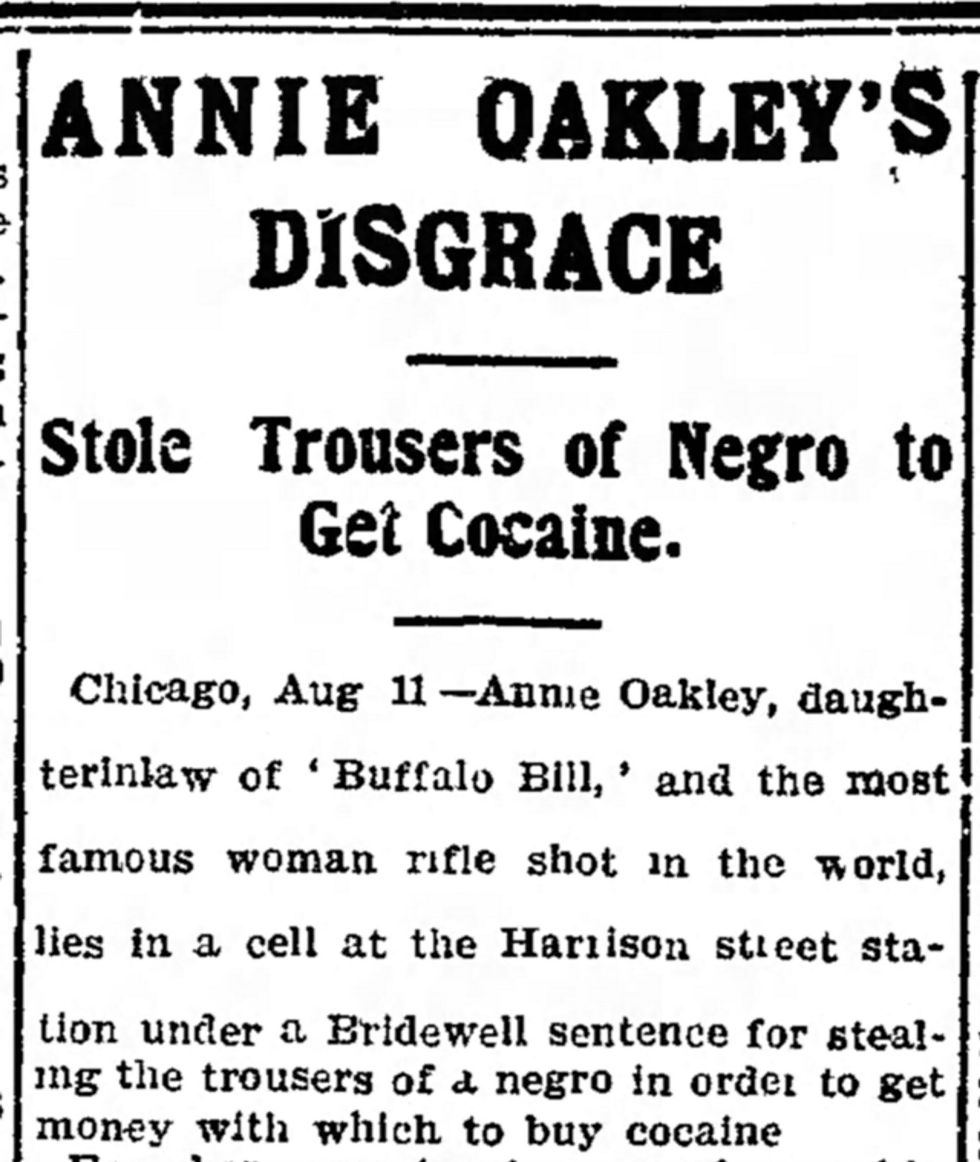

During the sweltering August heat of the summer of 1903, Annie Oakley—"Little Miss Sure Shot" herself—stole the pants of a black man and sold them for a few cents at a Chicago pawnshop. Oakley had become addicted to cocaine, and she stole to feed her habit.

As newspapers around the country picked up the story, readers learned more about the tragic fall from grace of a woman once considered virtuous—one of the best examples of what a woman in America could and should be. Oakley was thrown in jail at Chicago's Harrison Street Station for a few days, and then she was taken to court. She stood before the judge and begged for mercy.

"I plead guilty, your honor, but I hope you will have pity on me," the famous sharpshooter told the judge with tears in her eyes. "An uncontrollable appetite for drugs has thus brought me here. I began to use it years ago to steady me under the strain of the life I was leading, and now it has lost me everything. Please give me a chance to pull myself together."

The judge considered her words for a moment before deciding to give her that chance, but perhaps not in the way she wanted. He banged his heavy gavel and said, "A good long stay in the Bridgewell will do you good." Oakley was dragged away, sobbing, by the court's officers and thrown into the city's House of Corrections.

Poor Annie Oakley. Recent years had not been easy on her.

"The striking beauty of the woman whom the crowds at the world's fair admired is now entirely gone," wrote a reporter for the Muscatine, Iowa, News-Tribune. "Although she is but 28 years old, she looks almost forty." The Reading, Pennsylvania, Times newspaper continued the sad story. "The prisoner's husband, Samuel Cody, died in England. Their son, Vivien, is now with Colonel Cody at the latter's ranch on the North Platte. The mother left 'Buffalo Bill' two years ago and has since been drifting around the country with stray shows."

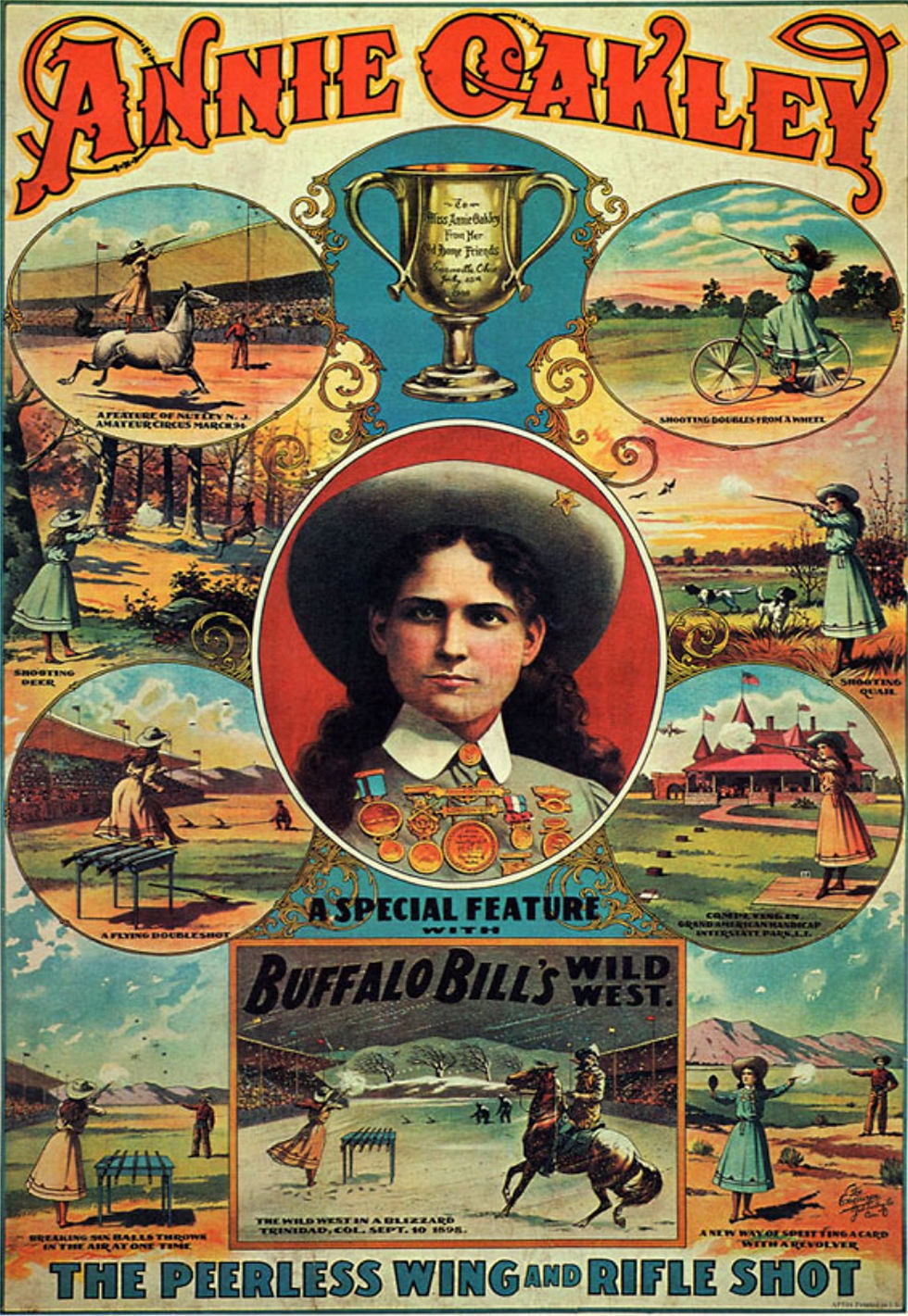

I'm willing to bet dollars to donuts that you didn't know that Annie Oakley, former sharpshooting star with Buffalo Bill's Wild West, was a cocaine addict who stole a black man's pants to feed her habit and that she was arrested for the crime and thrown in a Chicago jail. And there is one very good reason you weren't taught about that in school and it wasn't a scene in Irving Berlin's Annie Get Your Gun: It didn't happen.

Newspapers across the country reported everything mentioned above. I find references to Oakley's addiction and arrest in nearly every major newspaper in every state in the country throughout August of 1903. Consider this small sampling of headlines compiled from various papers, all within a week of the August 11th incident:

Very few papers ran anything to the contrary. One notable exception is the Greenville, Ohio, Democratic Advocate—Annie Oakley's hometown paper.

The Democratic Advocate reporter pointed out a few problems with the story as reported. The first is that the woman arrested for the theft of a black man's pants to fuel her cocaine habit in Chicago had given her name, not as Annie Oakley, but as Elizabeth Cody. Elizabeth claimed that her husband, Samuel Cody, had died a few years prior in England, but Annie Oakley's husband Frank Butler was alive and well and was presently staying at Nutley, New Jersey. "Mrs. Butler," the paper informed its readers, "is not a cocaine fiend, and even if she was, has plenty of money with which to purchase any quantity of of the drugs. Annie Oakley was never married to Sam Cody, the only husband she ever had was the present Frank E. Butler, a gentleman and true sportsman. The reporter who wrote the above item, was certainly under the 'fluence of dope and was probably writing up one of his own experiences. Her legion of friends in Darke county refute the story and are willing to gamble that 'Little Sure Shot' has been lied about."

This was, of course, the case. Annie Oakley wasn't a cocaine fiend. She hadn't stolen a poor black man's pants, and she hadn't pawned said trousers to fund her habit. A few of the papers that ran the story printed terse retractions.

When reporters realized that Annie Oakley was not in a Chicago jail, but shooting at the Jackson Club in Paterson, New Jersey, she was asked about the affair. She regarded the whole thing as "an awful mistake." A Paterson reporter commented that "her character is irreproachable, and the absurdity of the carelessly mistaken identity is apparent to everyone in this part of the country, though undoubtedly far from amusing to the lady in question."

Frank Butler sent a letter to Justice Caverly in Chicago, asking the judge if there was anything he could do to have his wife's name removed from the official records. According to the Chicago Tribune, the woman who had stolen the pants and had ended up in court had simply given the wrong name, causing all of the press reports. Mailing the judge a clipping of the New Jersey paper proving his wife's whereabouts, Mr. Butler asked, "I hope that you see now that it was not the real Annie Oakley that you fined. If it is still on the docket as Annie Oakley, can you have it changed?"

Soon, Oakley filed suit against each newspaper that had carried the false story. "The terrible piece ... nearly killed me," Oakley said. "The only thing that kept me alive was the desire to purge my character." For the next six years, Annie Oakley was not a sharpshooter or performer, she was a plaintiff, forever in one courtroom or another defending the good name she had spent a career building. Of the 55 lawsuits she initiated, Annie Oakley won or settled all but one. The money she was awarded varied from a couple of hundred dollars against smaller papers in smaller cities to $27,500 against William Randolph Hearst's big Chicago newspapers. Hearst had sent a private detective to Oakley's hometown of Greenville, Ohio, to try to dig up dirt to use against the famous sharpshooter in court, but the same citizens who refused to believe the story from the moment they read it also refused to rent a room to Hearst's investigation, running him out of town before he could spend a single night.

The settlement money awarded to Annie Oakley for those 54 cases was not enough to make up for the revenue she lost because for those six years she was not out entertaining thousands and thousands of spectators with her unerring precision with a rifle. But the money wasn't the most important thing to Annie Oakley. Her name and reputation were more important than money could ever be. Oakley was so effective at clearing her name that today even the many fans of Little Sure Shot and lovers of the American West, in general, have forgotten about the entire sordid affair. Even the newspapers that had printed the story, had been sued by Oakley, and had lost thousands of dollars to her couldn't help but respect the woman who fought so hard to restore her good name. The Hoboken, New Jersey, Observer, which had carried the initial story in full, years later mailed Oakley a flattering piece on her later shooting. "Although you dug into us for three thousand dollars at a time when three thousand dollars was a large sum with us," the editor wrote on a letter enclosed with the clipped piece. "— you see we still love you."

As for what started the entire thing? It turns out that the woman who was arrested in Chicago on August 11, 1903—the one who had stolen a black man's pants, pawned them off, and used the funds to purchase cocaine—wasn't Annie Oakley. She wasn't Elizabeth Cody. She wasn't a sharpshooter or a beloved American icon or the daughter-in-law of Buffalo Bill. She was a burlesque dancer named Maude Fontenella. But on stage, she used the name "Any Oakley."

Comments