Speaking of Shad Reminds me of Fish

- Matthew Kerns

- 11 hours ago

- 5 min read

In April 1876, "Texas Jack" Omohundro was in the home stretch of a marathon. He and Buffalo Bill Cody were eight months into a grueling dramatic tour that had begun in Philadelphia the previous August.

By the time the troupe arrived for their three-night stand in Rochester on April 10th, they had already traversed the Eastern Seaboard, dipped deep into the South through Virginia, Georgia, and Alabama, crossed into Texas, and battled a Northern winter through the Midwest and Ontario.

They had played nearly eighty cities in eight months—a relentless schedule of train whistles, stage lights, and "Indian dramas."

While the troupe was stationed in Rochester, Jack took a hard-earned break from the theater for a different kind of performance. On the afternoon of April 12th, Jack was spotted on the Rochester Aqueduct in the company of a local giant: Seth Green.

The setting was as much a marvel as the men. The Second Genesee Aqueduct (known today as the Broad Street Bridge) was a masterpiece of 19th-century engineering, a massive stone structure designed to carry the Erie Canal directly over the Genesee River.

Standing on this industrial landmark were two men who represented the bridge between the wild frontier and modern science. Jack, the quintessential cowboy and explorer who had guided the Earl of Dunraven and shared campfires with George Bird Grinnell, found a kindred spirit in Seth Green. Known as the "Father of Fish Culture" in North America, Green had established the continent's first fish hatchery in nearby Caledonia and was arguably the most famous conservationist of his era.

The Rochester Times-Union (then the Union and Advertiser) captured the scene of the Scout and the Scientist "whipping" the canal waters:

"Finding our distinguished townsman and national benefactor, Seth Green, engaged in the gentle art of casting a fly... In company with Mr. Green, and exchanging views with him on the knack of giving a right delivery to the fly, was another distinguished American... Mr. J. B. Omohundro, or, as the admirers of the Indian drama prefer to call him, 'Texas Jack'."

The reporter noted that Jack, while perhaps more famous for his skill with a rifle and tomahawk, "would hold his own among ordinary disciples of Izaak Walton*." Despite their combined expertise, the muddy, shallow waters of the canal offered no prizes. The article playfully mocked the pair for "catching no salmon in dirty water a few inches deep," but the true value of the moment wasn't in the catch—it was in this shared moment between two masters of the outdoors.

While Jack was on the aqueduct with Green, Buffalo Bill Cody was likely blocks away, spending precious time with his family at their Rochester home. Among them was his five-year-old son,Kit Carson Cody.

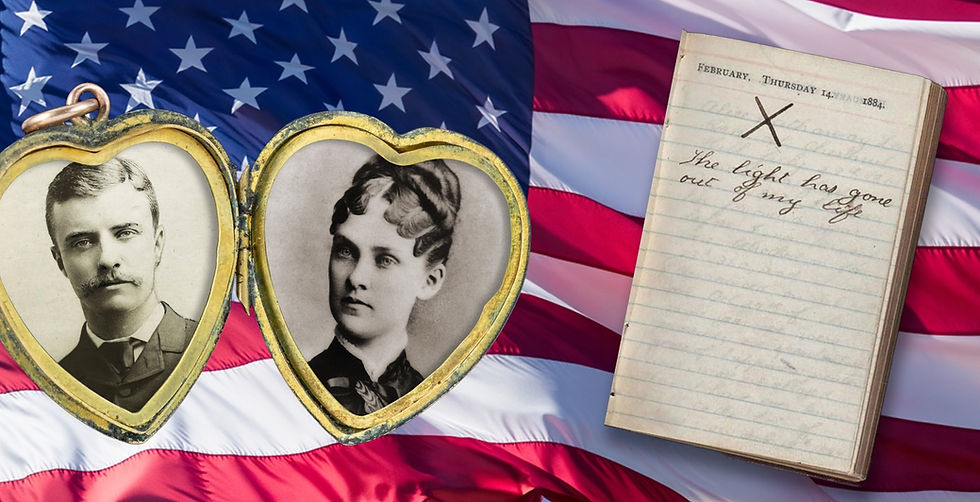

This peaceful afternoon of fly-fishing and engineering marvels was a brief, bright spot in an exhausting season, but it would also be one of the last moments of normalcy for the "Scouts of the Plains." Just one week later, on April 20, 1876, Kit Carson Cody died of scarlet fever. Cody, who was performing in Springfield, Massachusetts, that night, rushed home just in time to hold his son as he passed. He famously sent a telegram to his best friend, Texas Jack, with the heartbreaking words: "My only darling boy is dead."

The lighthearted fishing trip on the Genesee was the final respite before the wind left Cody’s dramatic sails. The troupe wrapped up the tour on June 3rd in Wilmington, Delaware, and the two legends never performed together again. Looking back at that April afternoon on the aqueduct, we see a rare, quiet glimpse of Jack at his most authentic—a man of the western wilderness, even in the heart of an Eastern city, standing between the old world of the scout and the new world of the scientist. *English writer, Best known as the author of The Compleat Angler.

Rochester Times-Union of Thursday, Apr 13, 1876 · Page 2

Fly-Fishing in Rochester Waters

Seth Green and Texas Jack Whip the Erie Canal, but Get Never a Rise

Yesterday afternoon, as the hands on public clocks were approaching the hour of six, a reporter observed a little knot of people gathered on the aqueduct which carries the waters of the Erie Canal over the Genesee River at this point.

Not knowing but that one more unfortunate had been found in the turbid waters, he immediately made his way to the spot, only to be agreeably disappointed and have his fears dispelled by finding our distinguished townsman and national benefactor, Seth Green, engaged in the gentle art of casting a fly—an art in which, it is scarcely necessary to inform our readers, Mr. Green has few rivals and no superiors on the American continent, if indeed in the world.

In company with Mr. Green, and exchanging views with him on the knack of giving a right delivery to the fly, was another distinguished American who is sojourning in this city for a few days—we mean Mr. J. B. Omohundro, or, as the admirers of the Indian drama prefer to call him, "Texas Jack".

Mr. Omohundro, although not professing to be as skillful with the fly-rod as he is with the rifle and tomahawk, would hold his own among ordinary disciples of Izaak Walton. If there had been either:

“Trout or salmon, Playing at backgammon,”

in the canal yesterday, there can be little doubt that they would have been lured to their destruction by the nice judgment and snowflake-like fly of Texas Jack.

If some of the trout fishers of the State who intend to try their skill with the rod at the coming State Sportsman's Convention had witnessed the exhibition which our reporter yesterday had the good fortune to behold, they would have possessed themselves of points which would have enabled them to gain distinction at the coming meeting in Geneseo.

We feel it our duty to impart to our readers such technical knowledge of the fly-fisher's art as could be gathered in a few minutes' observation. We feel the more impelled to pursue this course, because:

“Now is the time, While yet the dark brown water aids the guile, To tempt the trout.”

But, as the late James Thomson was transmitted to posterity, a delightful passage in which the anglers’ art is set forth in immortal verse, it will probably be more agreeable to our readers if his lines are substituted for prose. We make no apology for transferring to these columns a description which will be recognized as that of a master:

Just in the dubious point, where with the pool Is mix'd the trembling stream, or where it boils Around the stone, or from the hollow'd bank Reverted plays in undulating flow, There throw, nice-judging, the delusive fly; And as you lead it round in artful curve, With eye attentive mark the springing game. Straight as above the surface of the flood They wanton rise, or urged by hunger leap, Then fix, with gentle twitch, the barbed hook: Some lightly tossing to the grassy bank, And to the shelving shore slow dragging some, With various hand proportion'd to their force.

The above contains precisely what our reporter learned were the best advices even now known to the craft, and answer for fishing in American waters as well as for those on the other side of the Atlantic.

As veracious narrators of the whole truth, we must say, that notwithstanding the assiduity with which Messrs. Green, Omohundro and Tagunay plied the rod on the state waters yesterday, they were not once electrified by the tug and rush of a hooked trout or bass.

It is a loss to the city that a visitor should be disappointed of a successful day's fishing here, but no one should be deterred from stopping over on that account, for in a few weeks, when the roily water of the Genesee has become clear, an angler who will fish the Rapids as thoroughly as the waters of the aqueduct were fished yesterday by Messrs. Green and Omohundro will not, like them, be disappointed—if, indeed, they were disappointed at catching no salmon in dirty water a few inches deep.

Comments