The Cowboy

- Matthew Kerns

- Apr 23, 2021

- 7 min read

From The Spirit of the Times, March 24, 1877. Written by Texas Jack, this piece was included in the show programs for Buffalo Bill's Wild West as an introduction to the cowboy.

The cow-boy! How often spoken of, how falsely imagined, how greatly despised (where not known), how little understood? I've been there considerable. How sneeringly referred to, and how little appreciated, though a title gained only by the possession of many of the noblest qualities that go to form the more admired, romantic hero of the poet, novelist, and historian: the plainsman and the scout. What a school it has been for the latter? As “tall oaks from little acorns grow," and tragedians from supers come, you know, the cow-boy serves a purpose, and often develops into the more celebrated ranchman, guide, cattle king, Indian fighter, and dashing ranger. How old Sam Houston loved them, how the Mexicans hated them, how Davy Crockett admired them, how the Comanche feared them, and how much you “beef-eaters” of the rest of the country owe to them, is such a large-sized conundrum that even Charley Backus and Billy Birch would both have to give it up. Composed of many "to the manner born," but recruited largely from Eastern young men, taught at school to admire the deceased little Georgie in his exploring adventures, and though not equaling him in the “cherry-tree goodness," more disposed to kick against the bulldozing of teachers, parents, and guardians.

As the rebellious kid of old times filled a handkerchief (always a handkerchief, I believe), with his all, and followed the trail of his idol Columbus, and became a sailor bold, the more ambitious and adventurous youngster of later days freezes onto a double-barreled pistol, and steers for the bald prairie to seek fortune and experience. If he don't get his system full, it's only because the young man weakens, takes a back seat, or fails to become a Texas cow-boy. If his Sunday-school ma'am has not impressed him thoroughly with the chapter about our friend Job, he may be astonished, but he'll soon learn the patience of the old hero, and think he pegged out a little too soon to take it all in. As there are generally openings, likely young fellows can enter, and not fail to be put through. If he is a stayer, youth and size will be no disadvantage for his start in, as certain lines of the business are peculiarly adapted to the light young horsemen, and such are highly esteemed when they become thoroughbreds, and fully possessed of "cow sense."

Now, cow sense has a deeper meaning than it seems to have, as in Texas it implies a thorough knowledge of the business and a natural instinct to divine every thought, trick, intention, want, habit, or desire of his drove, under any and all circumstances. A man might be brought up in the States swinging to a cow's tail, and, taken to Texas, would be as useless as a last year's bird's nest with the bottom punched out. The boys grow old soon, and the old cattle-men seem to grow young; and thus it is that the name is applied to all who follow the trade. However, inside the trade the boys are divided into range-workers and branders, road-drivers and herders, trail-guides and bosses.

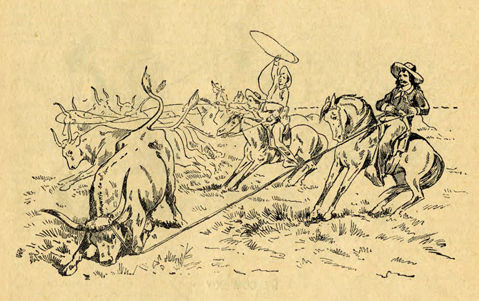

As the railroads have now put an end to the old-time trips, I will have to go back to a few years ago to give a proper estimate of the duties and dangers, delights and joys, trials and troubles, when off the ranch. The ranch itself and the cattle trade in the State still flourish in their old-time glory, but are being slowly encroached upon by the modern improvements that will in course of time wipe out the necessity of his day, the typical subject of my sketch. Before being counted in and fully endorsed, the candidate had to become an expert horseman, and test the many eccentricities of the stubborn mustang; enjoy the beauties, learn to catch, throw, fondle—oh! yes, gently fondle (but not from behind)— and ride the "docile" little Spanish-American plug, an amusing experience in itself, in which you are taught all the mysteries of rear and tear, stop and drop, lay and roll, kick and bite, on and off, under and over, heads and tails, handsprings, triple somersaults, stand on your head, diving, flip-flaps, getting left (horse leaves you fifteen miles from camp—Indians in the neighborhood, etc.), and all the funny business included in the familiar term of “bucking;” then learn to handle a rope, catch a calf, stop a crazy cow, throw a beef steer, play with a wild bull, lasso an untamed mustang, and daily endure the dangers of a Spanish matador, with a little Indian scrape thrown in, and if there is anything left of you they'll christen it a first-class cow-boy. Now his troubles begin (I have been worn to a frizzled end many a time before I began); but after this he will learn to enjoy them—after they are over.

As the general trade on the range has often been written of, I'll simply refer to a few incidents of a trip over the plains to the cattle markets of the North, through the wild and unsettled portions of the Territories, varying in distance from fifteen hundred to two thousand miles—time, three to six months—extending through the Indian Territory and Kansas, to Nebraska, Colorado, Dakota, Montana, Idaho, Nevada, and sometimes as far as California. Immense herds, as high as thirty thousand or more, are moved by single owners, but are driven in bands of one to three thousand, which, when under way, are designated "herds”. Each of these have from ten to fifteen men, with a wagon driver and cook, and the “king-pin of the outfit”, the boss, with a supply of two or three ponies to a man, an ox team, and blankets, also jerked beef and corn meal—the staple food; also supplied with mavericks or "doubtless-owned" yearlings for the fresh meat supply. After getting fully underway, and the cattle broke in, from ten to fifteen miles a day is the average, and everything is plain sailing, in fair weather. As night comes on, the the cattle are rounded up in a small compass, and held until they lie down, when two men are left on watch, ridin' round and round them in opposite directions, singing or whistling all the time, for two hours, that being the length of each watch. This singing is absolutely necessary, as it seems to soothe the fears of the cattle, scares away the wolves, or other varmints that may be prowling around, and prevents them from hearing any other accidental sound, or dreaming of their old homes, and if stopped would, in all probability, be the signal for a general stampede. "Music hath charms to soothe the savage breast," if a cowboy's compulsory bawling out lines of his own composition, such as these:

Lay nicely now cattle, don't heed any rattle,

But quietly rest until morn.

For if you skedaddle, we'll soon give you battle.

And head you as sure as you're born

Can be considered such.

Some poet may yet make a hit,

Of the odds and ends of cow-boys' wit.

But on nights when old "Prob." goes on a spree, leaves the bung out of his water barrel above, prowls around with his flash box, raising a breeze, whispering in tones of thunder, and the cow-boy’s voice, like the rest of the outfit, is drowned out, steer clear, and prepare for action. If them quadrupeds don't go insane, turn tail to the storm, and strike out for civil and religious liberty, then I don't know what strike out means. Ordinarily, so clumsy and stupid-looking, a thousand beef steers can rise like a flock of quail on the roof of an exploding powder mill, and will scud away like a tumbleweed before a high wind, with a noise like a receding earthquake. Then comes fun and frolic for the boys!

Talk of “Sheridan's ride, twenty miles away,” that was in the daytime, but this is the cow-boy's ride with Texas five hundred miles away, and them steers steering straight for home; night time, darker than the word means, hog wallows, prairie dog, wolf, and badger holes, ravines and precipices ahead, and if you do your duty three thousand stampeding steers behind. If your horse don't swap ends, and you hang to them till daylight, you can bless your lucky stars. Many have passed in their checks at this game. The remembrance of the few that were foot loose in the Bowery a few years ago will give an approximate idea of three thousand raving bovines on the warpath. As they tear through the storm at one flash of lightning, they look all tails, the next flash all horns. If Napoleon had a herd at Sedan, headed in the right direction, he would have driven old Billy across the Rhine.

The next great trouble is crossing streams, which are invariably high in driving season. When cattle strike swimming water they generally try to turn back, which eventuates in their "milling," that is, swimming in a circle, which if allowed to continue, would result in the drowning of many. There the daring herder must leave his pony, doff his toggs, scramble over their backs and horns to scatter them, and with whoops and yells, splashing, dashing, and didoes in the water, scare them to the opposite bank. This is not always done in a moment, for a steer is no fool of a swimmer; I have seen one hold his own for six hours in the Gulf after having jumped overboard. As some of the streams are very rapid, and a quarter to half a mile wide, considerable drifting is done. Then the naked herder has plenty of amusement in the hot sun, fighting green head flies and mosquitoes, and peeping around for Indians, until the rest of the lay-out is put over—not an easy job. A temporary boat has to be made of the wagon box, by tacking the canvas cover over the bottom, with which the ammunition and grub is ferried across, the running gear and ponies swam over after. Indian fights and horse thief troubles are part of the regular rations. Mixing with other herds and cutting them out, again avoiding too much water at times, and hunting for a drop at others, belongs to the regular routine.

Buffalo chips for wood a great portion of the way (poor substitute in wet weather), and avoiding prairie fires later, varies the monotony. In fact, it would fill a book to give a detailed account of a single trip, and it is no wonder the boys are hilarious when it ends, and, like the old toper, "swears no more for me," only to return and go through the mill again.

How many though never finish, but mark the trail with their silent graves, no one can tell. But when Gabriel toots his horn, the “Chisholm Trail” will swarm with cow-boys. “Howsomever we’ll all be thar,” let’s hope, for a happy trip, when we say to this planet, adios!

J.B. Omohundro

Texas Jack

Comments